“They Wanted to Erase My Language — I Chose to Write in It” — Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o » Capital News

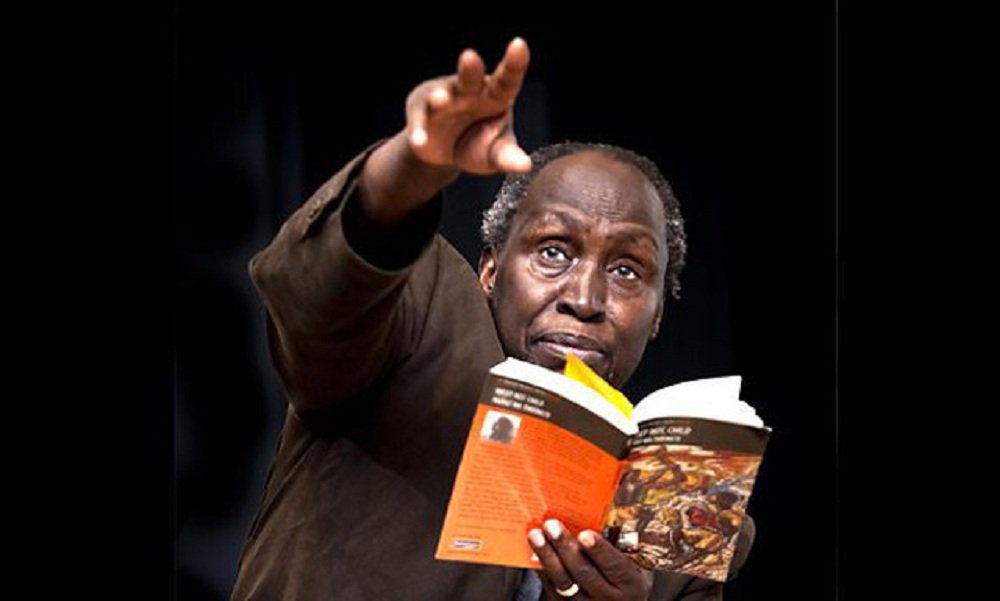

Prof. Ngugi wa Thiong’o was precise with his words, and the wordsmith delicately weighed them before he let them roll off his tongue.

“My wife was raped, not sexually violated. There was penetration, and you can’t downplay that in your paper,” he told me with a chilling tone from his Nairobi Hospital bed in 2004.

The night before, the renowned author and his wife had been brutally attacked in their suite as they slept, having broken his political exile after President Kibaki’s National Rainbow Coalition whitewashed Mzee Daniel Arap Moi’s independence party in the 2002 elections.

Being the News Editor of The Standard, Kenya’s oldest paper—then growing in leaps and bounds—I had this stubborn habit of checking into the office by 6 a.m., first to take stock of the ‘night’ stories and prepare the docket for the morning editors’ meeting chaired by the Managing Editor. But I also had this selfish reason to be early; it was inevitable if you wanted to beat Nairobi’s heartbreaking morning traffic and get good, close, and safe parking slots in this maddening city.

As I listened to the good professor drop his carefully considered choice of words slowly and with an obvious punch to my stomach, my mind ran wild with imagination and guilt. Wa Thiong’o was not an ordinary Kenyan old man—no, he was a hero, and many a knee knocked against the other when he spoke. It did not matter that, far from the power of his written word, orally he was slow, and spoke haltingly and with a concealed stammer.

But given the celebrity status he enjoyed as an unbowed human rights activist, former political detainee, exiled senior citizen, and the sensational and euphoric reception Kenyans had rolled out as a ‘welcome home’ message upon his return, the violent night raid and desecration of his wife was a cruel twist—indeed, an unpalatable anti-climax.

The sad news captured the attention of global media networks and cast a daunting long shadow on Kenya’s ‘second liberation’—a movement Prof. Thiong’o supported and for which he paid a painful price behind the greyish walls of Kamiti Maximum Prison. Every Kenyan face bowed in shame. The attack needled even the most hard-core hearts, right from the jubilant NARC politicians to the new KANU opposition members now adjusting to the cold benches in the corner of defeat.

My head bowed in shame as I listened to him, having walked into the newsroom to find the landline ringing shrilly before the warm rays from the heavens above our ‘City in the Sun’ broke through the morning cloud and mist of that cold August. I just recall trying to explain to the grand warrior—who fought his fights with the might of his pen and its endless ink jets—that we were a family paper and couldn’t afford to be graphic in reporting sexual assault.

Remember, our sister station, like all Kenyan media, had skirted around the heinous crime, as is ethically required of them—first, to lessen the trauma on the victim and to be sensitive to the larger readership and viewership.

“Do you know by downplaying the magnitude of this vile crime you have been unjust and unfair to Njeeri and myself?” said the Professor. His insistence, choice of words, and struggle with intonation to the level of a near-whisper pricked my heart as it unmasked the toll on himself and Njeeri. I found myself apologizing profusely but still confused as to what effect explicit description of what happened that night would have had on the Ngugi family—and on our audiences.

I couldn’t tell him, but being a newsroom veteran with a career soaked in episodic sad experiences—when the wording, logic, facts, or framing of stories ruffled many feathers, especially in the corner office and within the general ranks of the population—I knew that if we took that route, some suited executives would have had us for breakfast, lunch, and dinner all rolled into one.

Still, as I listened to him, several things ran through my mind about the wordsmith. Though at that stage it had not become clear that the attack was an inside job—which police traced to his family and those who welcomed his reception and lodge—but that is a well-documented story to be retold another day.

As a student of Literature with good early exposure to Ngugi’s books—especially A Grain of Wheat, The River Between, Ngugi Detained, Three Days on the Cross (which contains the hilarious story of the Mercedes burial), and his first, The Black Hermit—I knew how vividly, poetically, and deeply the old man could describe a scene. His choice of words took you there—you literally walked in his footsteps, savouring the sight and the scent.

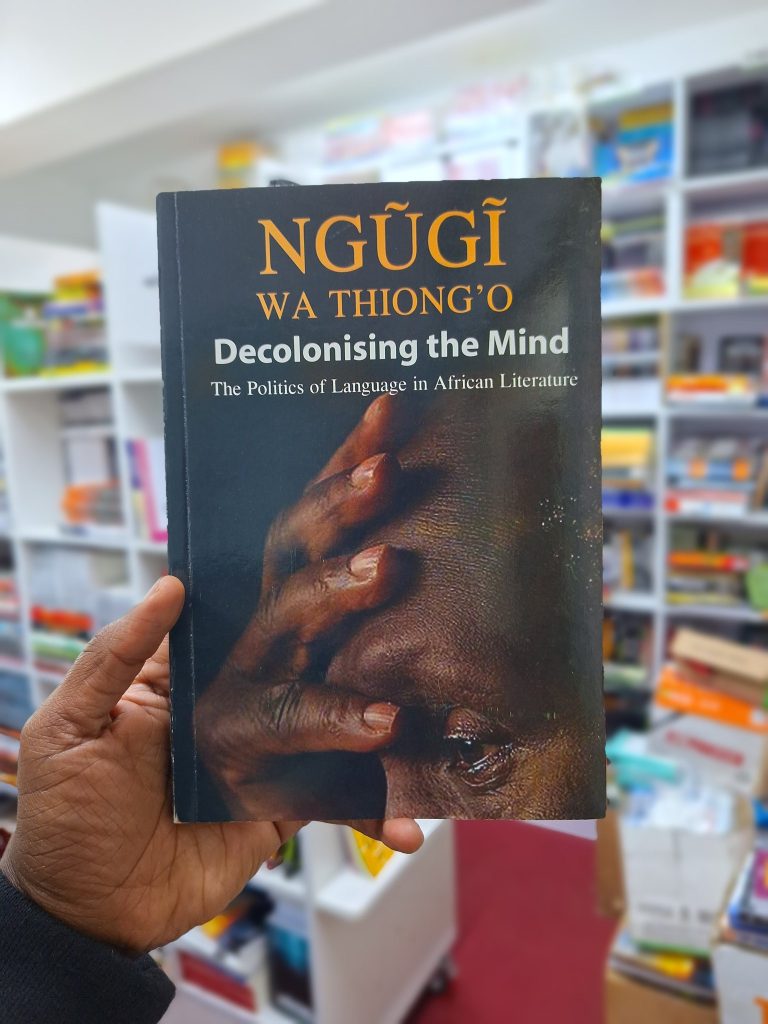

I also knew how he had lately turned to writing in his mother tongue, Agikuyu, as a tribute to his rich heritage and in defiance of colonization, as discernible in another of his stellar books—Decolonising the Mind.

I also remembered hearing from one distinguished member of his former Literature Department at the University of Nairobi—where he exchanged scholarly bouquets and barbs with more restrained and less adventurous (with the pen!) members like Prof. Henry Indangasi and the late Prof. Chris Wanjala—that he wrote his Master’s degree thesis in Agikuyu. If memory does not fail me, it was hard to get a supervisor, and I’m not sure, but it could have been the late Prof. Micere Mugo, with whom he would later flee into exile to avoid the crash of KANU’s knobkerrie on their ‘hot’ heads.

So here I was, a subdued but otherwise hot-blooded editor listening to Prof. Ngugi while simultaneously trying to imagine how his straight reporting of the crime would have sounded in my mother tongue—as well as his. A quick image of the gallant art collector and founder of Gallery Watatu (before the destructive fire of the ’90s) came to mind. He taught us how to quickly stop someone from using the expletives shit or fuck. “Just ask them to repeat the same word in their mother tongue and you will never hear it again.” But your guess is right—I could never tell that to Prof. Ngugi. First, because I truly revered him. But also because he was speaking from a hospital bed—obviously traumatized and in pain.

Fast-forward to 2019, when the literary icon walked into our newsroom at I&M Building, Nairobi. He had aged. He spoke more sluggishly, walked unsteadily—but the mind was still as sharp as a razor. The entire newsroom gave him a standing ovation—the only welcome by the dreary and unassuming journalists that came close to that accorded to Barack Obama in 2006, when the then cantankerous Government Spokesman dismissed him as a “mere Senator.”

In this visit, he was brought to the editorial meeting room where I was chairing the morning docket. He took his seat as we suspended planning the coverage of the day’s stories. In our midst was a Kenyan hero.

As if there had not been any time gap between our telephone conversation in 2004 and this hallowed day in 2019, the Professor sought to decolonize our minds by speaking about how, sadly, in the neocolonial era we had been made to feel inferior and guilty about our Black heritage, rich culture, and language.

He painted a bleak picture for the African continent’s cultural and linguistic heritage as we strove to look and speak like our tormentors and colonisers.

He asked if we do not feel shame when we correct and judge each other on how well we speak foreign languages and pronounce their words. “When you tell these modern-day colonists you speak Kikuyu, Dholuo or Kalenjin, they exclaim ‘Wow!’ But if you tell them you speak English or other Western languages, they ask you, ‘Why?’”

He explained that to them, the alien languages are a monopoly of a few and a ticket to respect and endorsement as ‘civilized’, and should only be accessible to a chosen few who drive the agenda of modern-day political, economic, and social imperialists and colonisers.

For a man famed for sneaking out the manuscript of his Ngugi Detained book from the confines of the haunted walls of Kamiti—which he described as a grey-coloured instrument of oppression Black Kenyans inherited from the colonist and continued to use against fellow Blacks—written on toilet paper!

The book captures the sad letter from his first wife Nyambura, whom he cruelly abandoned upon going into exile, informing him she had since delivered a bouncing baby boy (as he was arrested when she was pregnant). She also tells him, “Enclosed, please find new underwear, socks, toothpaste and toothbrush,” a chilling reminder of the dehumanizing and debasing nature of detention under both Presidents Jomo Kenyatta and his successor, Daniel Arap Moi.

Still in this book, the professor wryly recounts how, during his detention, he suffered a rotten tooth, went on hunger strike, cheated death, and only came to know that President Jomo Kenyatta had died long after the fact—thanks to the news blackout for political detainees like Raila Odinga and Koigi wa Wamwere. What shocked him most was that the golden carriage on which Kenyatta’s body rode for public viewing, and the expensive wooden coffin he lay in, were “gifts from the Queen of England—the symbol of Black exploitation and the thievery of the bourgeoisie class.”

As we mourn Prof. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, we must relook at him afresh—not just as a giant of letters but also as a victim of colonialism who, as mirrored through the characters in his books, endured the torturous and debasing era of British rule: detentions, killings, forced labour, and the uprooting of families from ancestral homes.

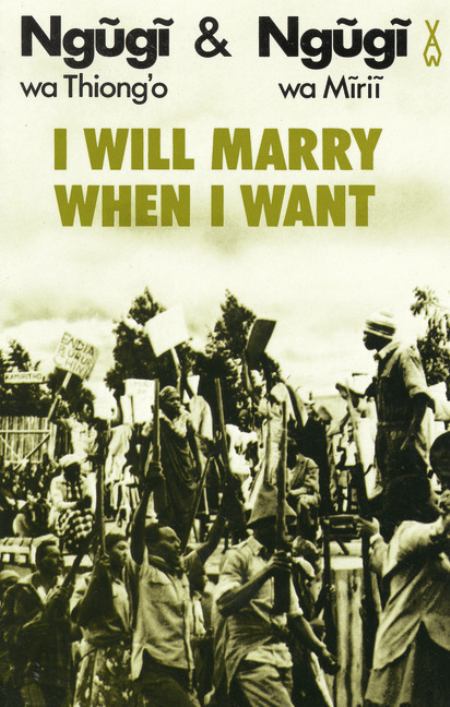

Yet, the boy born in 1938 would defy that grim history to join the prestigious Alliance High School. Then known by his baptismal name, James Ngugi, he would pen his first book The Black Hermit under that identity. But what would take him out of Kenya wasn’t exile alone—it was a string of politically charged literary works and fiery philosophy that climaxed with the Kikuyu play Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want), staged at his Kamirithu village. It was a daring satire, rich in meaning and symbolism, performed under the shadow of a draconian regime.

As fate would have it, decades later—and on Tuesday, 28th May 2025 to be exact—Ngũgĩ quietly left us. I say “quietly” because, many times in the past, reports of his death in the US would circulate, only for him to reappear days later with the witty reassurance that he was “as fit as a fiddle.” Which is why I feel the only story he never wrote—until now, as he transitions to the life hereafter—would have been: I Would Die When I Want.

Today, Kenya mourns. The literary world—which denied him the Nobel Prize in Literature—grieves. But somewhere in the clouds, the good old, witty, and sharp-minded professor is whispering in our ears: Weep Not, Child. He lived his life. He conquered his world. He kept tyrants and their agents awake. The bad omen of prison, exile, and literary vagrancy never dimmed the candle of his chivalry, gallantry, or valour.

It all started—and ended—in Kamirithu village. But the world was his stage.

Fare thee well, Kenyan icon of patriotism, with a spitting pen goaded by an intellectual mind par excellence.

Mr. Kipkoech Tanui is a veteran Kenyan journalist and former senior editor at The Standard Group, where he held key leadership roles including Executive Editor and Head of News. He currently serves as the Head of PR and Communication at the Kenya Red Cross Society.

[Note: This article was first published by Switch Media and republished here with permission.]