Pakistan’s Renewed Crackdown Forces Afghan Refugees into Uncertain Return » Capital News

Aug 12 – At the Torkham border, where Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa meets Afghanistan’s Nangarhar Province, the once-busy hub of trade and travel now echoes with scenes of quiet desperation. Tens of thousands of Afghan families—exhausted, anxious, and often without resources—are making the journey back to a homeland many fled decades ago, or have never seen. For most, it is not a choice but a forced return.

The exodus follows Pakistan’s revival of the Illegal Foreigners Repatriation Plan in late 2023, triggering a nationwide crackdown on undocumented Afghan refugees. Thousands who sought shelter after the Taliban takeover in August 2021 are now facing arrest, detention, and deportation. In April alone, over 144,000 Afghans crossed back into Afghanistan, including nearly 30,000 forcibly removed. Enforcement has expanded to major urban centres such as Islamabad and Rawalpindi, where police raids have led to families being sent to deportation centres without legal recourse.

The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) has condemned the expulsions as forced repatriation in violation of international law, warning that women, children, the elderly, people with disabilities, and those at risk due to their professions are disproportionately affected. Former senator Farhatullah Babar has stressed that Pakistan’s lack of domestic refugee legislation does not absolve it of obligations under its tripartite agreement with Afghanistan and the UNHCR.

Particularly vulnerable are Afghan girls born and raised in Pakistan, many of whom have never been to Afghanistan. They now face life under a regime enforcing the world’s only nationwide ban on girls’ education. Safiya Aftab, Executive Director of Verso Consulting, called the policy “heartless,” while Elsa Imdad Hussain of the Centre for Research and Security Studies urged the adoption of a gender-sensitive refugee law—an appeal that has yet to be heeded.

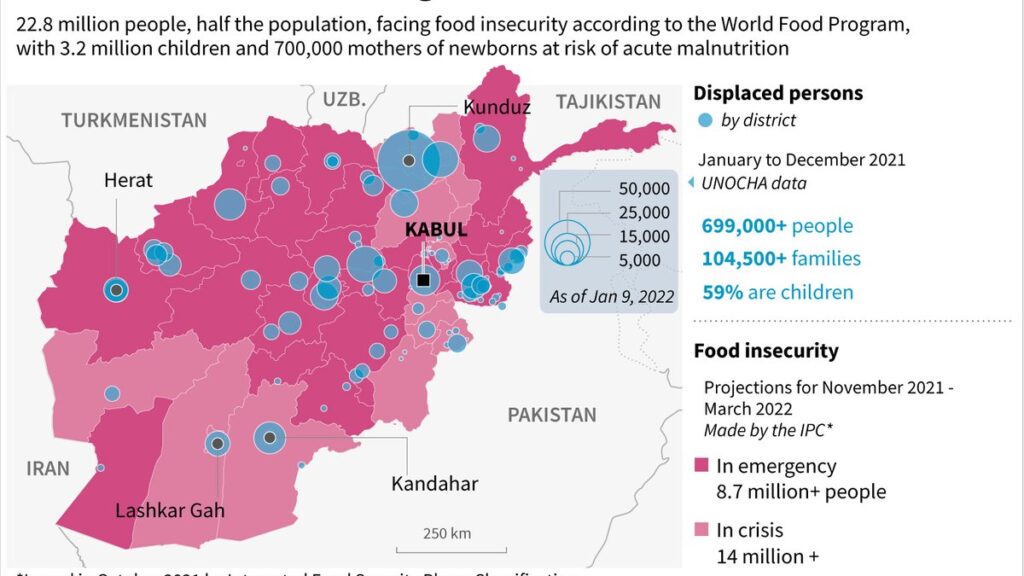

Returnees arrive in an Afghanistan grappling with overlapping crises—economic collapse, climate disasters, and severe humanitarian shortages. Taliban authorities offer only limited support, leaving many families in tent settlements such as Moye Mubarak in Nangarhar with little more than uncertainty about their next meal. The policy has also heightened tensions between Islamabad and Kabul, with Afghan officials accusing Pakistan of using refugees as political leverage.

Economists warn of local fallout. Afghan refugees have long supplied labour to fragile markets in Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Their sudden removal, PTI’s Barrister Muhammad Ali Saif cautions, risks economic shrinkage and deepening mistrust.

Official records show 1.3 million Afghans hold Proof of Registration (PoR) cards and about 700,000 possess Afghan Citizen Cards (ACC) in Pakistan. Despite permissions allowing PoR holders to stay until June, reports indicate ongoing arrests and detentions. ACC holders, along with undocumented Afghans, are being prioritised for removal.

Visa renewal has also become more restrictive, with durations cut from six months to one and fees prompting many to pay agents inflated sums for expedited processing. UNHCR and the International Organisation for Migration have warned of what they call the planned relocation of registered Afghans from Islamabad and Rawalpindi.

Authorities have capped the amount of money families can carry out of Pakistan at Rs 50,000, forcing many to abandon their businesses and assets. Reports suggest that some Pakistanis are exploiting departures for personal gain, including through dubious property transactions.

The UNHCR has reiterated its call for Pakistan to halt the forced return of Afghan refugees, warning that deportees face heightened risks—especially women and girls under Taliban rule. On August 5, UNHCR spokesperson Babar Baloch noted that more than 2.1 million Afghans have returned or been forced back from neighbouring countries this year, including 352,000 from Pakistan. He stressed that forced deportation is not a viable or humane solution, echoing concerns from rights advocates and former diplomats alike.