Five key questions that remain » Capital News

Sep 15 – It was the submersible that promised passengers the trip of a lifetime. A chance to descend 3,800m (12,500ft) to the Atlantic depths to visit the wreck of the Titanic.

But last year, a dive by Oceangate’s Titan sub went tragically wrong. The vessel suffered a catastrophic failure as it neared the sea floor, killing all five people onboard.

The US Coast Guard is holding a public hearing on 16 September to examine why the disaster happened, from the sub’s unconventional design to ignored safety warnings and the lack of regulation in the deep.

Titan began its descent beneath the waves on the morning of 18 June 2023.

On board were Oceangate’s CEO Stockton Rush, British explorer Hamish Harding, veteran French diver Paul Henri Nargeolet, the British-Pakistani businessman Shahzada Dawood and his 19-year-old son Suleman.

Later that day, after the craft failed to resurface, the US Coast Guard was notified, sparking a vast search and rescue operation.

The world watched and waited for news of the missing sub. But on 22 June, wreckage was discovered about 500m (1,600ft) from Titanic’s bow. Titan had imploded just one hour and 45 minutes into the dive.

These are five key questions that still need to be answered.

Did the passengers know the dive was going wrong?

Those on Titan could stay in contact with the support ship, the Polar Prince, with text messages sent through its onboard communications system. The log of these exchanges could reveal if there were any indications that the sub was failing.

The vessel also had an acoustic monitoring device – essentially mics fixed to the sub listening for signs it was buckling or breaking.

“Stockton Rush was convinced that if there was an imminent failure of the submersible, they would get an audio warning on that system,” explains Victor Vescovo, a leading deep sea explorer.

But he said he was highly sceptical that this would have provided enough time for the sub to return to the surface. “The issue is how quickly would that warning happen?”

If there were no apparent problems during the descent and alarms failed to sound, those on board could have been unaware of their imminent fate.

The implosion itself was instantaneous, there would have been no time for the passengers to even register what was happening.

Which part of the Titan sub failed?

Forensic experts have been examining Titan’s wreckage to find the root of the failure.

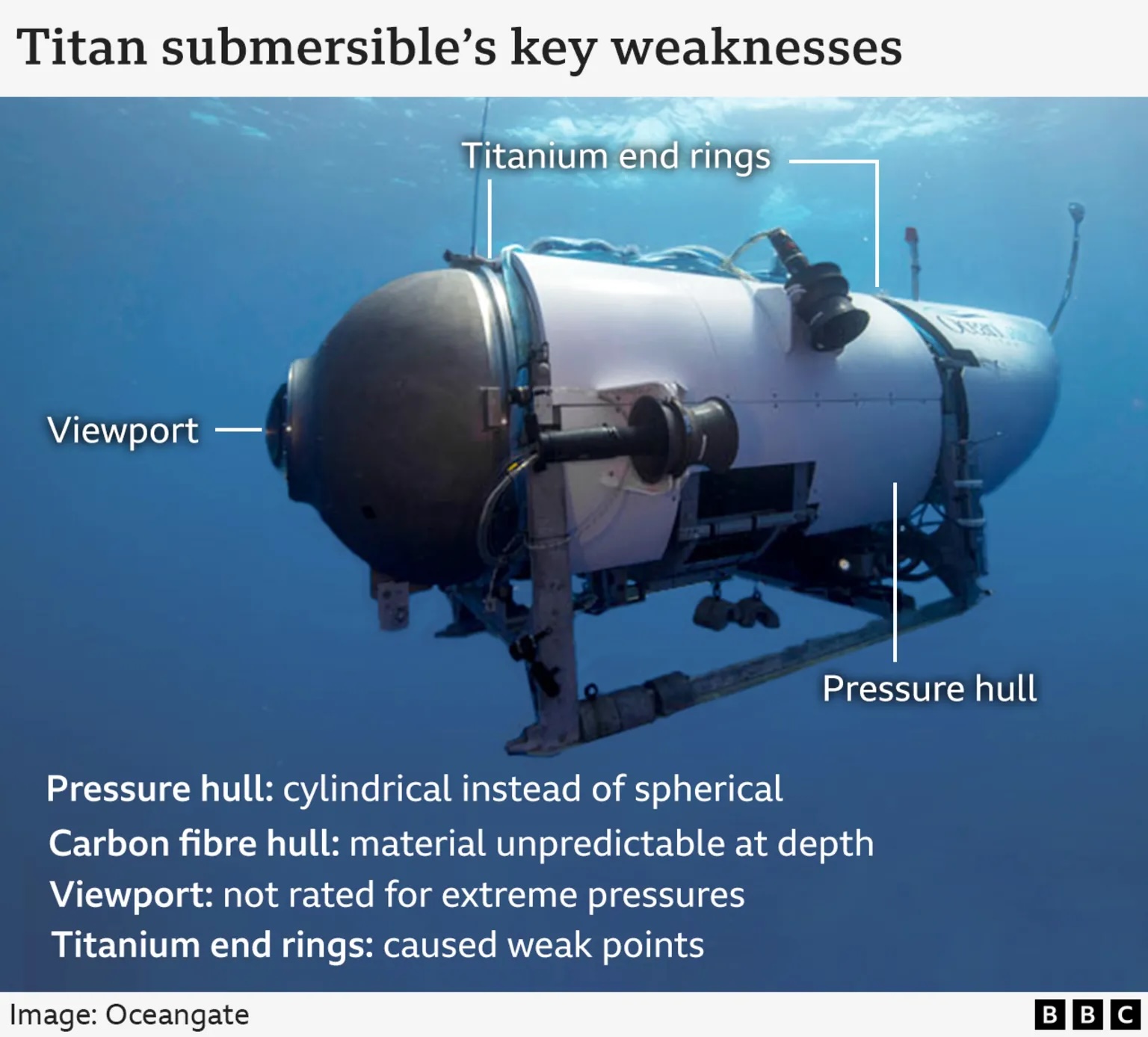

There were several issues with its design.

The viewport window was only rated to a depth of 1,300m (4,300ft) by its manufacturer, but Titan was diving almost three times deeper.

Titan’s hull was also an unusual shape – cylindrical, rather than spherical. Most deep-sea subs have a spherical hull, so the effect of the crushing pressure of the deep is distributed equally.

The sub’s hull was also made out of carbon fibre, an unconventional material for a deep-sea vessel.

Metals such as titanium are most commonly used as they are reliable under immense pressures.

“Carbon fibre is considered to be a material that is unpredictable [in the deep ocean],” explains Patrick Lahey, CEO of Triton Submarines, a leading manufacturer.

Every time Titan went down to the Titanic – and it had made multiple dives – the carbon fibre was compressed and damaged.

“It was getting progressively weaker because the fibres were breaking,” he said.

The junctions between different materials also gave cause for concern. The carbon fibre was attached to two rings of titanium, creating weak points.

Patrick Lahey said the commercial sub industry had a longstanding, unblemished safety record.

“The Oceangate contraption was an aberration,” he told BBC News.

Did ocean sounds distract from the search?

Ships, aircraft and remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) were scrambled to the Atlantic to try to find Titan.

A couple of days into the search, there were reports of underwater noises picked up by a search plane’s sonar, raising the possibility they were coming from the sub.

ROVs were sent to locate the source but found nothing.

It is still not clear what the sounds were – the ocean is noisy and even more so during an operation like this.