The Conscience Who Refused to Surrender » Capital News

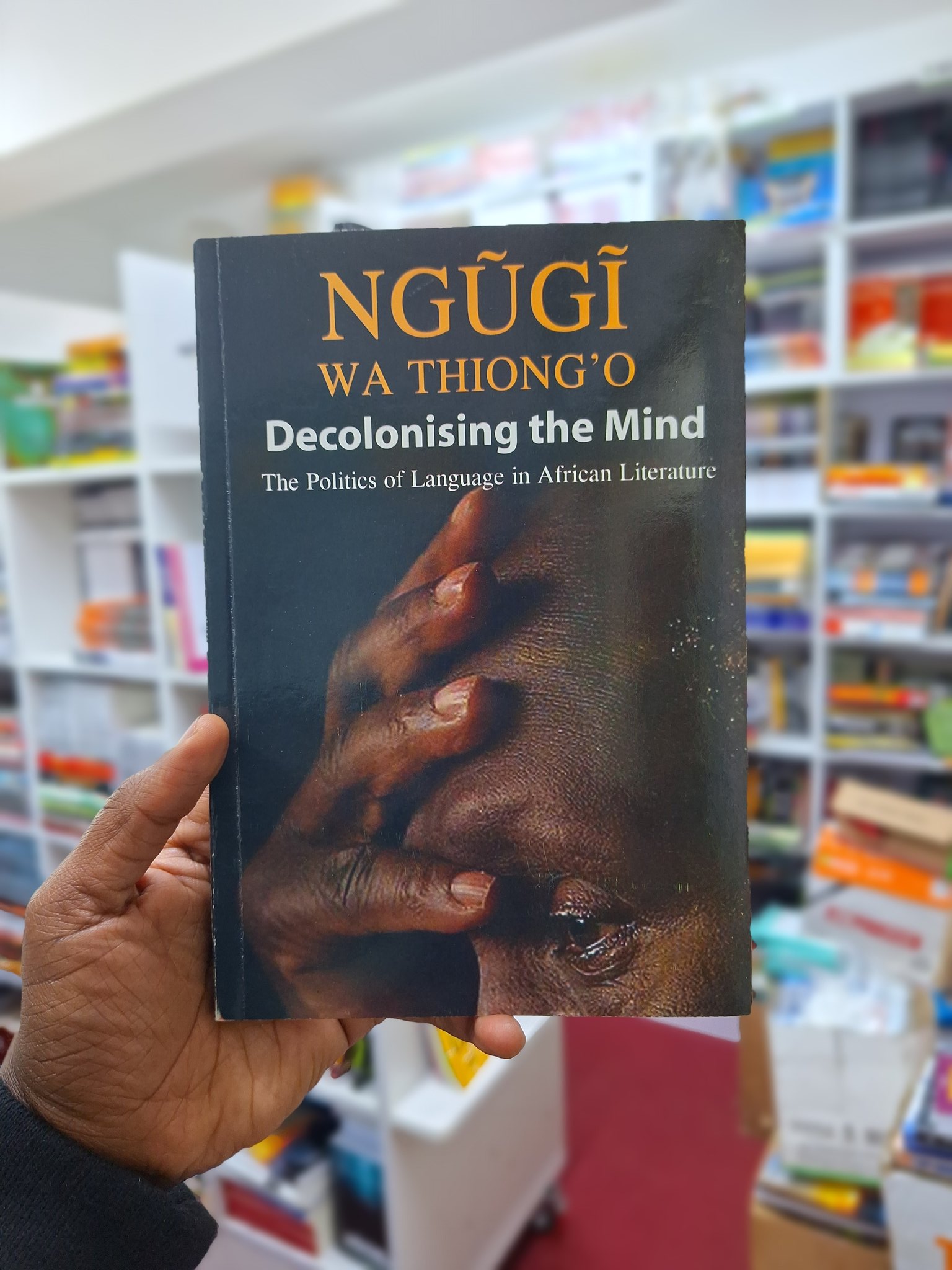

The passing of Prof. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o draws the curtain on the life of one of Africa’s most consequential literary and ideological figures. Ngũgĩ was not merely a writer—he was the towering conscience of our times, a colossus who dared to speak truth to power through his pen, his voice, and his life. From the dawn of Kenya’s independence, he inspired generations by confronting injustice, dissecting the contradictions of nationhood, and imagining a freer, more dignified Africa.

What distinguished Ngũgĩ was the authenticity of his Kenyan and African consciousness. He wrote from the continent’s imaginative core, positioning African experiences not as footnotes to global history, but as central narratives in the struggle for justice. He captured the pain, the betrayals, the dreams, and the fierce hope of a people navigating the aftermath of colonialism and the disappointments of post-independence leadership.

Marjorie Oludhe Macgoye, another prolific voice, shared this sensibility. Her widely studied poem A Freedom Song, with its haunting refrain “Atieno yo,” mirrors Ngũgĩ’s concern with injustice. Through the lens of a young girl’s exploitation, she illuminated the broader plight of the African girl child, expressing both a deeply Luo and universal African consciousness.

Ngũgĩ’s personal story, like his characters, was one of contradiction and courage. I recall a powerful talk he gave on the BBC World Book Club at the University of Nairobi Library in February 2019. He spoke about his time at Alliance High School—how the euphoria of learning from white teachers was violently shattered when he returned home to find his village razed and his family detained. The same civilisation that taught him truth in class was inflicting brutality in his community. The “mzungu” in the classroom was not the one wielding the gun in the village.

But this raw collision of hope and horror did not break Ngũgĩ. It fuelled his resistance. In A Grain of Wheat, Gikonyo—imprisoned just after marrying Mumbi—returns home to find her carrying another man’s child. Yet his turn to carpentry is not defeat, but defiance. It mirrors Ngũgĩ’s own journey: choosing to write in Gikuyu, enduring prison and exile, and still writing with clarity, courage, and hope. From that BBC encounter, I remember him recounting how his mother’s words guided much of his work: “No matter how long or dark the night is, dawn will surely come.”

Similarly, The River Between grapples with the tension between Christianity and African traditions—tensions still alive today. The ideological rift between Kameno and Makuyu captures our broader anxieties about identity and belonging. Muthoni’s defiance of her father’s Christian doctrine to undergo traditional initiation—only to die and declare that she has “seen Jesus” and become “a woman, beautiful in the tribe”—is a sublime moment of spiritual and cultural reconciliation. Ngũgĩ’s genius lay in such synthesis—refusing binary choices, embracing complexity.

His literature is not trapped in the past. It resonates deeply with today’s politics. Like Gikonyo before his release, or Ngũgĩ returning from Alliance, Kenyans entered the last election with high hopes. But expectations were quickly undercut by harsh reality. The promise of “no handshake” governance met the realpolitik of broad-based inclusion. In many ways, Ngũgĩ’s works remind us that resistance must not devolve into bitterness—it must evolve into constructive agency.

On the eve of Madaraka Day, the people of Homa Bay gathered at Raila Odinga Stadium, braving the chill not out of naïveté, but in stubborn hope. Their quiet vigil reflected the same spirit Ngũgĩ wrote about: that even amid contradictions, justice and transformation are possible. That even this regime, if broadened and anchored in principle, could deliver.

Ngũgĩ never gave in to disillusionment. He believed that resilience was the answer to betrayal. When hope is bruised—build. When promises are broken—organise. When power falters—hold it to account. This is the moral force of his legacy.

In 2022, the current regime made a bold promise: that if it failed to deliver, it should be voted out after one term. That promise must not be forgotten. But we must resist trivialising our civic responsibility through populist slogans and empty catchphrases. As 2027 nears, we owe it to ourselves—and to Ngũgĩ’s spirit—to take stock honestly and act decisively.

Prof. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o may have left us, but his words remain—loud, urgent, and uncompromising. He taught us that in the face of contradiction, the answer is not surrender, but struggle. Not silence, but truth. Not despair, but hope.

Rest in power, Prof. Ngũgĩ. You taught us to write, to resist, and to never lose hope.