From No Handshake to Political Survival, The Reality of Leading Kenya » Capital News

Being the president of Kenya is turning out to be one of the hardest jobs. Unless you’ve held the position, it’s difficult to grasp just how challenging it is. Otherwise, there would be no explanation for why presidents consistently choose to appease political elites at the expense of the voters—the very people who matter in a democracy.

President Mwai Kibaki, after a grand and promising start, found refuge in the Grand Coalition government. Even after controversially swearing himself in at night, he couldn’t hold on without sharing power, leading to constitutional reforms that redefined how presidents assume office. His successor, President Uhuru Kenyatta, abandoned the dynamic duo arrangement in his second term and sought political stability through a handshake with Raila Odinga, a move that cemented his legacy.

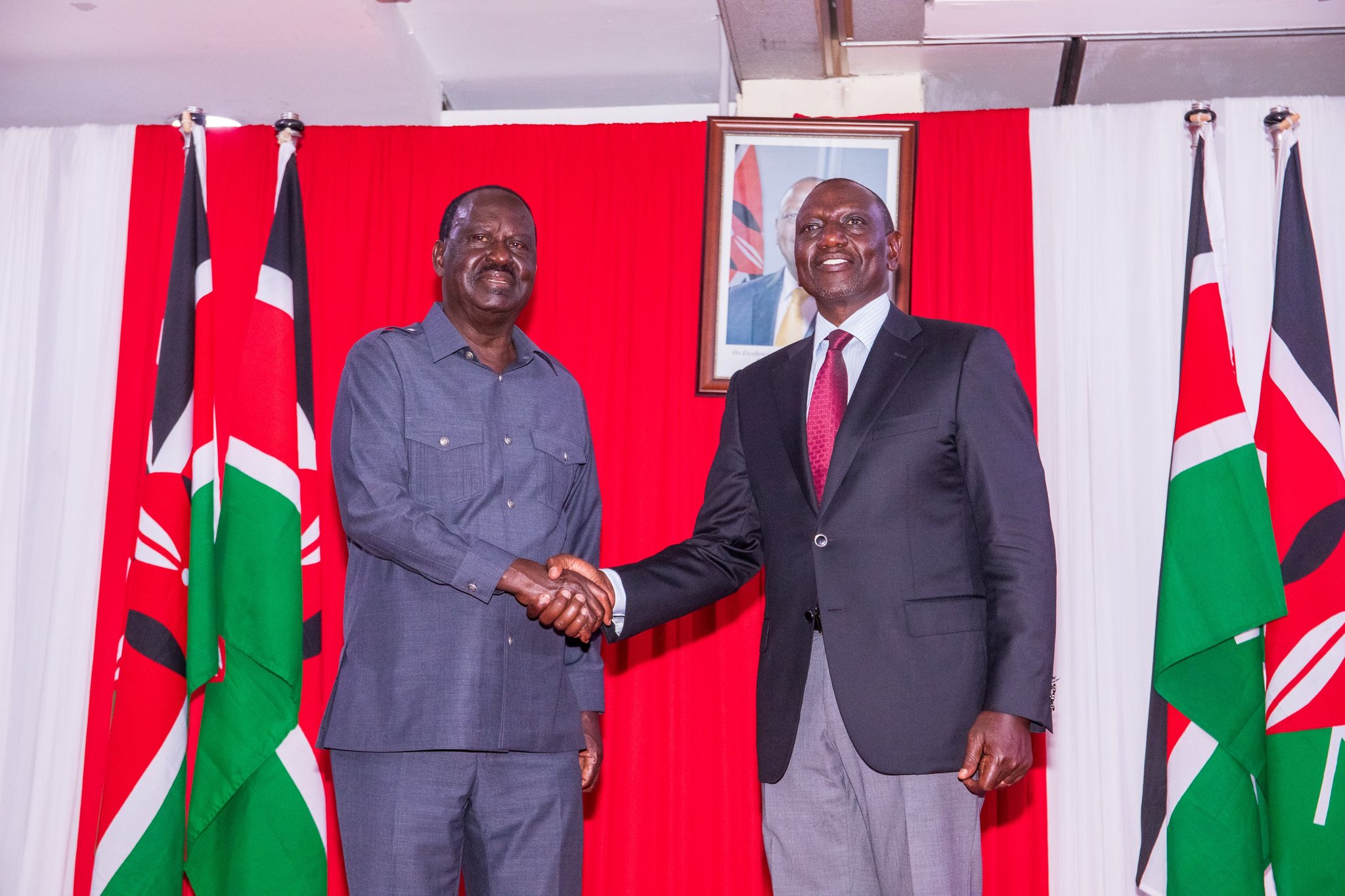

Then there’s President William Ruto, who spent over 20 years working towards the presidency, vehemently rejecting the idea of a handshake. Yet, today, he finds himself presiding over what he once condemned as a “mongrel” government—one where opposition figures are absorbed into the administration, and the government itself lacks clear opposition. His predicament is a testament to how circumstances often conspire against even the most resolute leaders.

Ruto and his allies despise this ‘nusu mkate’ arrangement, but they are here not by choice, but by necessity. The presidency, it seems, is only fully understood once one occupies it. Critics argue that this administration has taken the easy route of self-preservation, one that may cost it dearly. Instead of standing with Wanjiku, they have chosen to align with political elites—leaders with little grassroots support who, when the moment of reckoning comes, may abandon them.

The prevailing strategy appears to be the recreation of a summit of ethnic kingpins, akin to the ODM model of 2007. By bringing together regional leaders—some with minimal influence in their backyards—the government is effectively reducing millions of individual voters to ethnic blocs, believing these leaders can deliver votes en masse in 2027. This approach is as flawed as the so-called “tyranny of numbers” theory once peddled by political propagandists.

The reality on the ground is shifting. Kenyans are increasingly disengaging from ethnic politics. The struggles of the average citizen—soaring taxes, eroded wages, and the high cost of living—are fostering a collective consciousness that transcends tribal identity. Wanjiku is no longer thinking in terms of “our people”; she is thinking of shared struggles, regardless of ethnic background.

The political construct of Wamunyoro—the belief that Ruto will lose the Mt. Kenya vote and that Deputy President Rigathi Gachagua will emerge as the regional kingpin—is another misguided notion. The assumption that voters will act as a monolithic bloc in 2027 ignores the evolving political landscape. Increasingly, the electorate is tired of political elites and is inclined to vote based on individual merit rather than tribal loyalty.

This should mark the end of the outdated summit politics that treats voters as balkanized ethnic groups. If Ruto secures re-election in 2027, he will likely close the chapter on this generation of leaders. Any politician within a decade of Ruto’s age has 2027 as their last major opportunity. By 2032, Kenya should usher in a new generation of leadership.

To young and ambitious politicians: go wherever you must in 2027—Wamunyoro, Sugoi, Bondo, UDA, KK, ODM, DAP. Win elections, gain experience, and secure political ground. But after 2027, let’s see a fresh wave of like-minded leaders storm State House in 2032. The time for change is coming.

Dr. Hesbon Owila is a Media and Political Communications Researcher.